Perspectives in Criticism from Helen Shaw, our monster in the audience

New York, December 30 — The ATCA Perspectives in Criticism series that extends back to 1992 booked its latest session last month, November 11, 2022, the first day of the ATCA New York City conference “Reseated and In-Person”.

The 2022 speaker Helen Shaw joined The New Yorker as a staff writer in 2022. Previously, she was the theater critic at New York magazine and its culture vertical, Vulture. She has also written about theater and performance for 4Columns and Time Out New York and contributed to the New York Sun, American Theatre magazine, the Times Book Review, the Village Voice, Art in America, and Artforum. She was co-awarded the 2017-18 George Jean Nathan Award for Dramatic Criticism.

The full listing of Perspectives speakers includes critics, playwrights, performers, and others reflecting on the critical arts. Previous “Perspectives” speakers have included critics such as Maya Phillips, Lily Janiak, Diep Tran, Jason Zinoman, Michael Finegold, Henry Hewes, Frank Rich, Dan Sullivan, Robert Brustein, Eric Bentley, Clive Barnes, and many others.

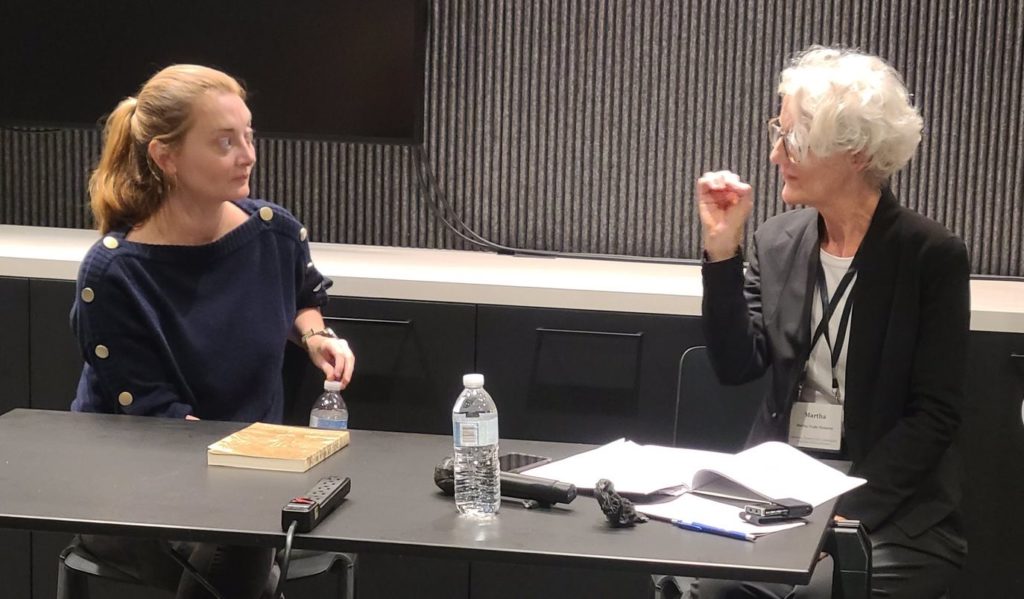

The 2022 offering was in the form of a conversation at Shaw’s request between Shaw and ATCA member and former Executive Committee Chair Martha Wade Steketee. Both served on the Drama Desk nominating committee together for several years, and currently serve on the Henry Hewes Design Awards committee.

Steketee: When you agreed to speak with us today when we met up on the street prior to an evening performance, we talked about a current professional shift for you. You’ve been writing for 20 years or so — she looks like she’s 10 but …

Shaw: There a lot of pain in the eyes.

Steketee: She’s written for Time Out and she was at Vulture where Jesse Green who we heard from this morning was before he moved to his current position at the Times. You’re now doing pieces that are more longer form, not 200-word reviews but “essay-y” kind of things. You’re at the New Yorker where, as we spoke briefly, it’s not overnight, its not having the immediate opening story. You had some feelings about that.

Shaw: I did. I did have some feelings about that. And it’s so wonderful that you talked about Jesse. I had been at New York magazine / Vulture for three years. I got that job right before the pandemic. the October before that March [of 2020] so I had barely been on the job by the time the job changed so radically, And before that I had been freelancing for a decade and a half, I was incredibly grateful that New York magazine did not immediately say: oh there’s no theater any more, sorry.

Steketee: That was a fun idea.

Shaw: Go away, yeah. And instead they kind of coached me along and taught me to be a journalist sort of on the fly. It was all very kind of them. And because Jesse had been at New York Magazine and then went to the Times. when the New Yorker job came up I called him and I said, what do I do? Do I leave? Do I not leave?

Steketee: Did they contact you? Was it something where you applied ….

Shaw: They needed to fill a hole. Alexandra Schwartz was moving into books and so the golden finger tapped me on the shoulder. I thought, well is there any reason not to go? Can you tell me? And Jesse was very … I admit I was looking for “go for it, girl” and instead he was very measured. He talked about writing at New York Magazine and being at an atelier. He said: when I was there, we fussed over every ivory button on the vest, and that he missed it. And that he said, you move into the hurly burly of the Times, and he said there were things about New York Magazine that he very seriously missed and that I should think seriously before I left such a warm and welcoming place. It was a big deal for me to leave that. My editor there, Chris Bonanos, who had been Jesse’s editor, is just a saint. So it was not an obvious decision, really. It was actually quite difficult. But what you and I were talking about on the street was the fact that one of the great things about New York Magazine – yes it’s an atelier because you’re working on the horn buttons or whatever with Chris — but because it has this internet, very rough and tumble, what have the Kardashians done this week, kind of briskness to their culture coverage, it meant that we were, Chris and I, were slamming up pieces really fast. I was able as a single person to cover the entire field because he was willing to edit me and put me up on line in like 45 minutes. It was very very fast. I posted one piece from the intermission of THE MUSIC MAN standing in the back with my computer on the phone with Chris, you know, it was a long intermission which made it possible until we got one piece up and then I went back and saw the second act. It had this kind of immediacy. It meant that there was really no gap, no gap at all, between the experience of the show, writing about it, and getting it into the world. And The New Yorker has not any … no one there knows who the Kardashians are, first of all, which obviously has a dark and a light side to that.

Steketee: They’re fine with that.

Shaw: They’re completely fine with it, bless them. And so they have a much longer time span in their view. Their horizon is so much farther. So when I post a piece there, it gets fact checked. [laugh] I was not fact checked at New York Magazine. I made up so many things in the middle of the night. I would bolt upright and be like, Gavin CREEL, you know …. [laughter] There have been some real doozies which we managed to conceal in the content management system.

But The New Yorker has a very different attitude about why you’re writing and what audience you’re writing for, and whether that audience has time shifted. You know? Are you writing for the future, are you writing for now? New York writes for now. Theater to me is so much a thing of the now that it is continuing to work through my brain that I am no longer having a conversation with the show that’s running, with an audience that’s going. Instead, I’m having a conversation with people not in New York, people who may never get to see the piece, or even people who like me get to their New Yorkers about six months late, and you fish them out of the giant pile and you open and you say, ah yes, the 1974 .. there was a wonderful piece.

Being part of that world has been constitutionally different because it means that you sit in the audience differently. And you are thinking about coverage so differently. And that has been an adjustment. I wouldn’t say it has been negative, I’m surprised at how long it’s taking me to adjust. The piece I just filed, which I pitched this morning, and they said, we would prefer that you would not pitch a thing in the morning of the day you want to post it. And I was like: I know that you said that, but certainly this time, the show is so good that we should … you know. I’m trying to drag them down to my level, like besmirch them with the dirty theater mindset and they can .. so anyway, their marble temple is getting a little mud on it thanks to me.

Steketee: You’re pushing them.

Shaw: Well, bless them. Again, being fact checked. Being fact checked. My favorite fact check question so far — I was reviewing AS YOU LIKE IT and I said that Rosalind flees a hostile court. And the fact checker said: why do you say it’s hostile?

Steketee: What was the play review that you were submitting from the back of thouse?

Shaw: You should all see it. CATCH AS CATCH CAN, It was at the New Ohio in 2018 and now it’s at Playwrights Horizons and the reason why I had to leap into action was that I found out it wasn’t being covered. I was working on my own at New York Magazine for a while, so I was sort of a one-man band there. If I didn’t cover it, nobody covered it. And now I’m adjusting to there being another person there, who has his own wants and needs, which is horrible. [laughter]

Steketee: That person is Vinson Cunningham.

Shaw: Vinson, yeah, genius. He was going to write about it and then decided to write about something else. I love this show, as I said, I’d seen it in 2018 and really fallen in love with it, and I was sitting there again with my husband, and he said it was like sitting next to a dog on a leash. The idea that I wasn’t going to get to write about it was so horrible. When I found out Vinson wasn’t going to write about it, I had to just go for broke. [Helen’s review was posted November 12, 2022.]

Steketee: Do you find at the New Yorker you’re able to have the freedom to write about both productions? I found the two productions so very distinct, hitting me. These are two productions of a new play, it’s a three hander, there are lots of nuance and complications to it … but how it was cast was very different. Three Caucasians in the first .. a woman and two men … and also a woman and two men in the current production .. but they’re all Asian.

Shaw: In Mia Chung’s script, these are white characters. She says you can either cast an all-white cast or you can cast an all-Asian cast, Up to you.

Steketee: But don’t mix and match.

Shaw: But this is not a color-blind situation. You are doing one or the other. That’s it! So yes in 2018 it was Ken Rus Schmoll production with Jeanine Serralles and Michael Esper and Jeff Biehl, and they were just incredible, so funny. And then in this production, it is .. they went the other way, they went with an All-Asian cast, and it is also stupendous, but it means that one of the things that’s happening in the family is that there is a lot of anti-Asian racism and so hearing Cindy Cheung say these horrible things about her son’s ex-wife …

Steketee: Who is Korean.

Shaw: Who is Korean, really torques the play in a very exciting way. So your question about — should I have written about both of them together …

Steketee: It’s not should but do you have the freedom to, at the New Yorker

Shaw: Yeah. With that longer horizon, 2018 is not a long time ago to them so of course they’d be happy if I had written a slightly more nuanced piece [laughter] but no … there’s no limit there, they’re very interested and curious people, and I’m very lucky I have an editor there named Valerie Steiker who loves the theater and really cares about it and is willing to work hard to get work out. The theater critic before me wrote twice a month, and Michael used to write twice a week, and I feel very uncomfortable when I don’t publish, I get very stressed out. And she’s like: chill out. I come from the world of Time Out, and in Time Out, especially when I was there in 2005 and 2006 and 2007 and in that period, we were almost encyclopedic.

Steketee: In the extent of what you covered, is that what you mean?

Shaw: It was a badge of honor that we covered things that the Times didn’t get to. That is still very ingrained in me, that sense that you are supposed to be covering so much that you are covering MORE than the Grey Lady. And every step you take into the future as we get into this current sort of terrible future that we’re in with so much less theater coverage than there was. Poor TIME OUT has been very limited by the people who own it now, The Voice is almost gone … then back .. then almost gone, now there’s the Voice on line. There is actually theater criticism at the Voice again which is thrilling. When I was at Time Out I thought that this is the world that I’m going to go into, we will cover everything. The further I get from that ideal, the sadder that is.

Steketee: We did an interview in 2017 that was a quirky little question and answer interview. I like a particular phrase you used then and wonder if you still feel this about yourself., if it still plays true. I asked you to review yourself as a critic. You said: “I was once called a ‘monster in the audience’ in a very angry bit of hate mail; I’m afraid that cuts to the heart of it..” Monster in the audience. I love that phrase and I dug the fact that we just left it there. How does that resonate with how you see yourself now?

Shaw: Monsters are things that are half one thing and half another thing. That’s what’s makes them frightening. The Centaur is a monster, and a Gorgon is a monster, and it’s because you’re mixing and matching things from the animal kingdom and the human phylum. As a critic, you are half one thing and you’re half another thing. And that’s awful because it means they can’t rely on you. They can’t rely on you as though you’re a “real” audience member because you don’t laugh the same way other people do, you don’t cry the same way other people do, and you’re taking notes and that’s creepy. And also, they can’t rely on you as the thing you think you are, which is an objective arbiter. They can’t rely on you as a friend, even though I know every critic feels that we are the strongest friends that the theater has. My god how many people in the theater go as much as we do, you know? When we look in the mirror, what I see is a booster. All I care about is theater, to the serious detriment of other things in my life, you know? And yet, really, there this antagonistic relationship. You’re part enemy, part friend. It is very weird and kind of uncanny for the theater to deal with us. So I think that’s what it was.

That piece of hate mail, I love that piece of hate mail so hard. It was the best one I ever got, it was when I was at TIME OUT, and I had reviewed a piece, and one of the actors in the show had written in this front and back page, single spaced, typed letter. And he just really was like, you don’t understand, all of our friends who have come to see the show say its really good, you’re wrong. And I almost, I should have kept it, but it went into some file at TIME OUT and is gone now. But the other thing was, he said “you are a monster in the audience” and I thought: well that is absolutely true. That is absolutely true. I’m not fish or fowl, I’m just this weird thing in the audience who isn’t the audience.

Steketee: So what often happens in these PERSPECTIVES IN CRITICISM things, you can talk about whatever you want to, but it’s reflections on the field, as dire as that can feel. Look at what’s happened, some of the cadre is landing interesting new agendas. From your vantage point now, or vantage point over the last couple of years, what do you think? Five years ago when we had our interview, you noted new people streaming in, trying new forms, trying new things, they’re doing audio reviews and stuff online and it’s looking different than what we’ve known in the past. It was a kind of hopeful response then. How you feeling now?

Shaw: I am reading this book right now by Ed Yong about animal senses called An Immense World: HOW A NIMAL SENSES REVEAL THE HIDDEN REALMS AROUND US. He talks about the umwelt and a person or creature’s umwelt is the things that they can perceive based on the senses that they have, so that .. if I’m … if a bumble bee and I are looking at a flower together some afternoon, the bumble bee can see that there’s a bull’s eye in the middle of that flower in colors that I can’t perceive, which guides the bumble bee to the center of the flower. And I look at the flower and it’s all red. And so that umwelt is just the senses that you have, that nothing is real to you, which is outside your senses. This is going to be a little bleak, but twitter has been one of my senses for the last 8 years, 10 years, 2011 I started my account there, but I didn’t use it very much.

Steketee: So you mean giving you feedback, you’re giving to and receiving.

Shaw: It’s how much I thought there was theater criticism. I would log into twitter every day, sad sad addiction, and I saw a lot of people talking about the theater, and I saw a lot of people linking to their reviews, and then I would go and read those reviews, and I had this sense that there was this very busy world full of writers, especially new writers, and that Twitter itself was a conduit for a type of criticism, a type of very live, crowd-sourced criticism. And we’re now thinking about the fact that Twitter might be gone by this week, everybody quit this morning, so, you know, it doesn’t really seem like there’s going to be something left for us. Which from a point of view of archives, we were talking about before, is absolutely horrifying. That we might actually lose this archive, it’s almost beyond belief. But more than that, it’s been … I believed until two weeks ago that I had an accurate perception of how much theater criticism there was in the world, and I thought that because my eyes were looking through Twitter. And if Twitter goes away, everything I saw through Twitter TO ME in my world of perception in my umwelt, will go away. And so I’m trying to think about: wait, how much actually will be left, how will we learn about it from each other? How will we read each other? How will I .. I have google alerts for everybody whose name I can remember, you know I certainly set that up right away. But for one thing, like Jackson McHenry has … has a name which it turns out there’s a guy in the Midwest who plays like lacrosse, so every morning I’m finding out about his lacrosse results, which is very useful. But still it’s like: what are we going to do? And so for me there’s this sense of a busy world being hushed, to steal a term. I at least, I Helen, will lose a sense of how much actual writing there is. So from that point of view, I find it very depressing, super depressing. And I also don’t know if the sense I was getting through Twitter is accurate. I know that all of us were reading each other, but how much were people reading us outside of that, I don’t know.

Steketee: Was it the algorithm at play.

Shaw: Exactly, were we just dancing for the algorithm, kind of thing, you know? And I don’t know what is true there. I do know that it is, we are going to rely heavily on things … this is very practical and boring thing about this different time scale that I’m on at the New Yorker, it means that often my pieces go up not on opening day. Just because they have to go through a finder set of mills to get to publication. Even when it goes up on line, I’m often several days after a technical opening. Which means that I am not collated and collected in the Playbill “what do the critics think” page. Boy I will tell you, that’s really important to me right now, because the way that my dad found out when I write a review is that he followed me on Twitter. And that is a person who trust me cares more than anyone else in the world about what I write. And yet, if I’m not being collated on Playbill and there is no mouthpiece through Twitter, I suddenly was like: how did we all used to read each other? And we all .. we did, didn’t we? So there’s this, that sense that I had in 2017 of multiplication, of fervent fervent multiplication, more people coming in, more people writing, just the sheer amount of stuff that was going up on HowlRound in 2017,

Steketee: The firehose of content, I participated in that.

Shaw: Yes, it really was. Was it too much? No! there can’t be too much theater criticism .. it’s like too much power! Impossible. So I think there’s no … so for me, that worries me. That gives me great pause and concern about where we’re headed in next, really in the next week.

Steketee: Wow. It sounds like things have happened with Twitter today that I totally …

Shaw: Everybody quit. Everybody quit.

Steketee: I asked you in that 2017 interview to review yourself as a critic in 140 characters. And you said: “Theater’s whole point is that it thinks the “long thought”; brevity ain’t in it. Plus, I lost a job once for my lack of Twitter presence,”

Shaw: It was the New York magazine job which I lost the first time I applied for it because they said: you have no social media followers. And I said: I have a very passionate social media follower in Lawrence, Kansas, his name is Michael Shaw, and he’s my dad. And they said: no, no, no. and then they hired Sara Holdren who was a great hire.

Steketee: Who spoke to us in this context a few years ago.

Shaw: Yeah. And then she quit theater criticism, which was just enraging.

Steketee: She did and she went back to directing.

Shaw: Every time we lose a theater critic it’s like an angel gets its wings chopped off, you know? [laughter] Sara Holdren, Scott Brown, hate it. Linda Winer retired.

At the New Yorker, they just named a new head of culture, Alex Barasch, who is moving from one position into another. that’s actually so exciting because genius-level intellect is going to kind of make those things possible for us, I think. My impression is that, no, the New Yorker is a place where there’s a lot of text, a lot of cut little umlauts and diacritic marks and we hyphenate “teen-age” [sigh],

Steketee: But you do it consistently!

Shaw: We’re so consistent. It is very much word-forward and it is, not just word forward but that there .. we are writing essays that would be recognizable to,..

Steketee: Robert Benchley.

Shaw: Exactly , in so many ways.

Steketee: I don’t mean that in a bad way at all!

Shaw: At New York Magazine, there was a bit more stuff that was collaboratively written with other critics. We would get into a talk and have a conversation and that would be posted as a piece. Jackson McHenry and I had a conversation about the film of WEST SIDE STORY I think the reason that was exciting is that I’m sure everyone in this room has this feeling about criticism because it is, I think it is universal to critics, is we are stuck in here with our own minds, and it is SO TIRING to have the same set of thoughts again and again. I will tell you that the person’s voice I am most sick of is my own. Why can I not write a paragraph without a colon, you know? That kind of exhaustion with yourself, when you do write in collaboration with someone, it’s so exciting, it’s so thrilling, and you wind up thinking a bunch of new and more interesting things because you had some person … in my case I was incredibly lucky because I had people like Kathryn VanArendonk and Mark Harris and Jackson McHenry, who seems to be shifting into the main critic role there. And so in that sense, yes, and we are going to do something like that at the end of the season, so that Vinson and I and Alexandra will have a kind of critical conversation. the three of us record that and then turn that into some kind of piece.

Vinson himself is very active in all the things I think are paracritical. I don’t know if you listened during the shutdown to the Richard the Second project that happened through the Public where he podcast. Vinson would be talking about the project and interviewing people, talking to the director and asking why did you make this choice, or talking to the dramaturg. And then you would hear an act in the play. Very useful, incredibly when you think about the critic as the person who provides the wall text in museum, it was such a smart delivery choice of delivery mechanism there. He’s particularly good at that.

He interviewed Suzan-Lori Parks at the recent New Yorker Festival and it was amazing. Some of the smartest thinking about playwriting that you’re going to get is happening in the space between Vinson and Suzan-Lori Parks.

So I still feel, and this is embarrassing because I am, as you said, 20 years into this, but I still feel like I’m working some things out, and that I would like to be better at writing before I crack it open into totally new sort of mechanisms and fields. But I certainly admire .. I was talking to someone last night about 3Views …

Steketee: Brittani Samuel, who is receiving an award from one of our programs, is one of the editors there. So describe them. There are some people here who might not know the premise.

Shaw: It was started actually by The Lillys. They had noticed that there were not enough women critics and they were very angry about that and started this project. They did a round of funding that support online women critics writing. The idea of the three views was that you would have three people writing about one show. Which is of course a gorgeous idea and takes us back to the good old days of the Sunday critic and when we had that kind of binocular vision, even at places at the Times. So it’s a great idea. Tri-nocular vision, that must be even better. And then the pandemic just walloped everybody but they were just getting up to speed. But one of the things they’ve done since they came back is they’ve really expanded what they think of as criticism, which included things like essays by the person who worked on the show. Lessing the first dramaturg worked in the theater with creators. You can be an “embedded critic” even if you’re working on the show. And my absolute favorite thing they did, is send three artists to a production, a Jess Barbagallo play, and they drew the production. One of them was Annie-B Parson who is the choreographer who directed their UTOPIA.

Steketee: Is the company she works in called Big Dance?

Shaw: As long as you promise to tell now one, I asked them once why they were called Big Dance Theater, when really they are very very theater, with some dancing. You get away with a lot when you tell people you’re a dancer. So artists went and drew their response to the production. She drew a family tree that connected the piece back to Moliere, which I stole the hell out of when I wrote about it. I was like, oh yeah, totally my idea that it was Moliere. No, no I got it from her!

And so there was this marvelous kind of three views, this idea that there’s no limit to what a critic response is. A critical response is simply looking at the thing, right? A piece of criticism is like when you’re at the eye doctor and they slide the lens in front and they say, is it better or is it worse? And that any lens you put in front of a piece is going to show you something about that piece you didn’t know. So why not put an artist in front of it, or put the set designer in front of it, or put a critic or a noncritic or some gorgeous stew of people in front of it. So that’s

Steketee: And more than one at the same time!

Shaw: So for me, that’s really the … when you think about .. are we going to use Instagram, is that actually going to be a method when Instagram is so allergic to text? So that’s one way to do it. You can have artists responding to pieces visually. And we still learn, you still learn about the shows. So .. I guess they actually make me feel a little hopeful. They make me feel less hopeful when I find out that they have no money, which .. if you’re looking for somewhere to put your money this Christmas … I would say that’s my source of optimism.

Artists are often very angry with us because we don’t speak to them. And we don’t. we speak to the audiences, right, we speak to audiences current, potential, future. And that’s difficult. That’s difficult to be an artists and say, ah I’ve entered into this exciting dialogue with this brain and you’re like, yeah, but we’re not really talking to you. I personally feel incredibly strongly that artists should not read their criticism until a year after the piece has happened.

Steketee: We had a talk with Pun Bandhu and Clint Ramos for our first panel today, a very exciting panel, and one theme that came out … there was moment where Clint in particular recalled a particular moment in a particular something he had done, and his frustration that critics didn’t see all the dimensions of the work he had created.

Shaw: It’s so awful to have created .. and have it missed, you know. Of course, they are right. What we do is, as I say .. I think that people who are critics could not love the field more. I think it’s the most pure expression of love for the field to be a critic. I also know that what we do is aggressive. There is a reason you have a weird relationship with your mother. Because your mother says when your hair looks bad. Right? Nobody else does. Everyone else is like, it’s cunning. You know? It’s not cunning, it’s a mullet. And so the person who says .. that’s rough, that’s rough, that is really hard, it’s a complicated relationship and its is not easy, it’s not supposed to be easy.

At the New Yorker, the ghost that lurks most for us in theater is John Lahr. John Lahr who is not a ghost, who is a presence, is the output-ease, those of us who are critics are always standing around in angry huddles talking about how fast he used to write. He just wrote an incredibly beautiful profile of Emma Thompson. there is a kind of conversation with his work.

I started there August 22 and this is the era of remote work. So what is the difference between working at New York Magazine and The New Yorker? I sit at the same table, I see the same shows, I scream for the same 8 hours at the computer until the review is done, you know, and then I file a different email address. Really? So I may be the wrong person to ask about the culture of the space because I’m very rarely there. I do know that one of the things that struck me as very strange at The New Yorker is that there is not, and Alex [Barasch] may be the person who provides this … there is not a field editor. There is not a theater editor to whom we all report. I have my editor, Vinson has his editor, Alex had her editor, and those people have other writers in their stable. But there is nothing .. and we coordinate in the sense that we send each other emails … but there isn’t .. if I don’t think of it to see a show, I’m not going to get SENT. There’s no assigning mind, do you know what I mean? That’s very strange to me. Because coming from TIME OUT, coming from the NEW YORK SUN, which did before that, ah THE SUN (wistfully), then a place called FOUR COLUMNS, then at NEW YORK, all of these places have a person whose job is there to think about the theater. And that is not the case at THE NEW YORKER. And that is one reason why when you open up a NEW YORKER you have no idea what you’ll find there. It might be a story about polar bears, and it might be a story about the theater. Because there is no one person pushing the agenda of theater. So that means that I have become that pushy person. And I am very irritating, I’m happy to do it. But it is that … its something that I worry about.

Steketee: Didn’t you say that the general editor calls you once a week or once a month?

Shaw: David Remnick loves a phone call.

Steketee: It seems like that’s an interesting .. might not be a specific directional thing .. but he has built this community and he checks in with all his people.

Shaw: That’s the thing. You do have this sense. There are so many brilliant people. I went to an “ideas meeting” and, oh my dears, I went swaggering in on Zoom, and I thought, I’ve been to ideas meetings before, I know how to pitch an idea. And then people started talking and I thought, oh right, this is THE NEW YORKER. Oh my god. And one of the ideas, which I’m just going to spoil for you all right now, was the Indian Ocean. And I didn’t know anything about the Indian Ocean. I was supposed to spitball among these geniuses about the Indian Ocean. And so I crawled back into my theater hutch, you know what I mean, and I backed well into the back, and I’ve been very cozy there ever since.

— Transcribed, heavily “linked,” and lightly edited by Martha Wade Steketee

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.